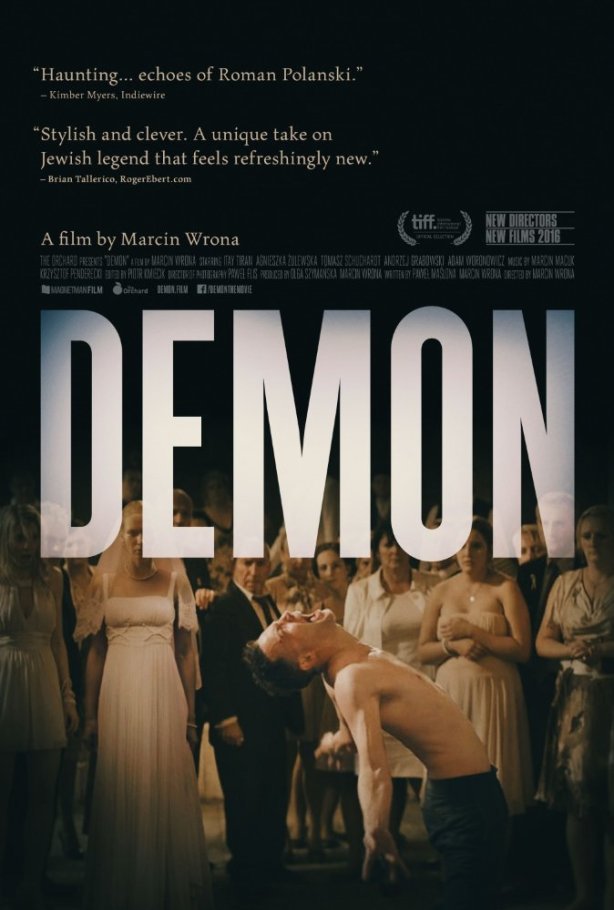

An exorcism of the collective Polish guilt, in earth tones and with a lot of dancing. Directed by Marcin Wrena, who killed himself right after.

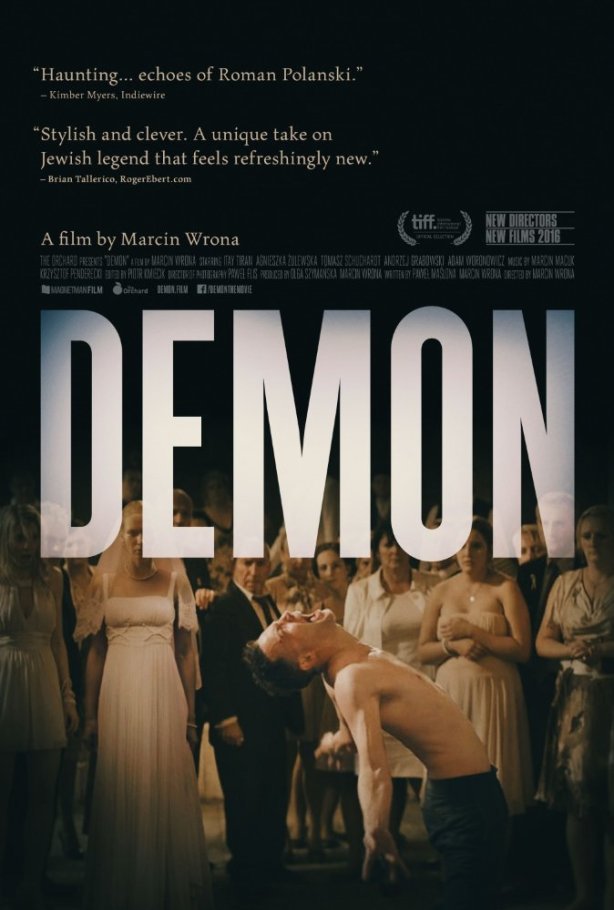

An exorcism of the collective Polish guilt, in earth tones and with a lot of dancing. Directed by Marcin Wrena, who killed himself right after.

Think of a film, any film. Yes, it is probably in this one. Director Pálfi György had the brilliant idea to make a movie entirely made up of scenes form other movies. The result is a story cut from more than 450 films and series – a nightmare in terms of copyright, one would imagine. But Pálfy managed to avoid legal toss and turn by declaring his film educational material for film students and releasing it as a free attachment to scholar Balázs Varga’s book about the film.

I have nothing but admiration for Pálfi, and whoever saw his Taxidermia probably knows why. However, despite the idea bordering on genius and the joy of watching this film, I was also very much disappointed. It seems that after having come up with such a nice premise, the author did not have the patience to come up with a story worth telling. And this is such a huge miss, as the possibilities were literally endless, he could have told ANY story. Instead, we get a quite disappointing cliché of boy meets girl they fall in love and misunderstanding comes between them. But this is still not the worse part, at least not what bothered me most. It was the annoying sexism and the portrayal of women – or, should I say, the Woman. One could argue that this might be one of the points of the film: how it’s the same old story, the same old characters, over and over again, and we still love them. So ok, if the point was to illustrate that Hollywood or film in general is a sexist cliché, well done. Still, I would have much preferred it if we got a different, stronger and more nuanced female character cut together from all the weak ones. Or if we got a male character who is not a thug.

But no, women are flirty singers who just want to get married and taken care of, while men chase after them and physically win them over from the competition and make them into trophy wives. After that women cook, clean, iron, have babies and wait for their husbands (who work long and hard, of course) in vain, having the audacity to have a headache when he comes home drunk and wakes them to have sex. Then the guy believes the first guy who suggests his wife is cheating… although, honestly, when would she have the time with all that cooking and ironing? And when a strong guy has doubts, he hits women, but suffers while doing it. Ok, women hit back but when they do, they turn alien monsters. Furthermore, when hurt in love, men join the army to blow stuff up and repeatedly shoot each other, while women take long baths to the music of Twin Peaks (no complaints here).

And the most painful was to watch genuinely original characters that Hollywood and film in general managed to create being cut into these ultimate cliché roles – when Björk seems to be saying a cheesy „I do” to a marriage proposal, that really hurt. And when there is a big dance scene without Christopher Walken, that hurts too. How could that happen?

But all and all, if one loves film, one just cannot stop watching and enjoying this avalanche of films coming our way. All the classics are there, but it was especially exciting to see some old time favorites like Twin Peaks, La Haine, Blue Velvet, La Boum (healthy humans born in the eighties might remember that as Sophie Marceau’s first film, so sweet and so eighties cool…), Monthy Python (at least two movies), Scenes from a Marriage, Dear Hunter, Annie Hall, The Double Life of Veronique, Pi, Irreversible, Natural Born Killers, Dangerous Liaisons, and so, so much more. Plus, the delight of the many Hungarian classics popping up here and there. The music also deserves special mention, even though we all know the selection by heart, it was nice to hear all the classic soundtracks again.

A huge missed opportunity which nevertheless should not be missed by anyone who loves film.

I can’t remember the last time I saw a Polish film in color. No complaints, though. Especially not with Ida, a film of such emotional intensity in its quiet seriousness that one is reminded of Kieslowski and Fellini all at once. The beauty of the cinematography is absolutely breathtaking, it emphasizes the bleak, desperate yet playful mood and atmosphere emerging around two women in Poland in the sixties. Anna is a young Catholic nun, raised in an orphanage and about to take her wows when she meets Wanda, her long lost aunt, former Communist activist, now a judge with the allures of an existentially tormented libertine. The two set out to uncover a dark family secret which will change both of their lives and make them reconsider who they are. There is something unique and exquisite in the way the “usual” Jewish family drama unfolds. There are no big words; no loud accusations from the victims and no remorse from the perpetrators. All is just so matter-of-fact that one hardly even notices when the sadness creeps up and starts taking over, presenting a quiet, calm argument to which no counter-argument is possible. But the best part is Anna’s face through all this and her gradual blossoming into a strong(er) woman, acting and deciding her own fate in full knowledge of who she is and what she is renouncing when renouncing the world. There is closure for Wanda too, one that comes as natural as her movements when putting on a Mozart vinyl and opening the windows…

Ida stars two amazing actresses, Agata Kulesza and Agata Trzebuchowska, and was directed by Pawel Pawlikowski, a literature and philosophy graduate who no doubt deserves more attention now that he has found his true artistic voice in his native language (his previous attempts in Enlish were by far not as memorable as this one).

Two of the best films I have seen this year share something utterly rare: they are both sincere and insightful reflections on mortality. Tarr Béla’s The Turin Horse and Michel Haneke’s Amour are two different, yet still surprisingly similar films. They are similar first of all in the austerity and perfect craft of their cinematic language. Tarr and Haneke are two masters with mature style or vision and a pace unique to them. This makes both films formally flawless and stunning. In terms of storytelling, the two directors are quite diffeent, however. While Tarr is prone to portray reality as if only an excuse to push metaphysical and poetic thoughts through, Haneke is much more interested in the strangeness and layers inherent in reality itself. This two tendencies are reflected in the two films as well. Tarr offers an existential-cosmic interpretation of the mortal condition, while Haneke examines in grim and realistic detail the actual “happening” of dying. In spite of this difference, I believe that the two films complete each other and can enter into an interesting dialogue in one’s head if we allow them too. It is as if Tarr’s film was a more philosophical-abstract re-interpretation of the fact of death examined by Haneke.

I am going to start with a bold statement: not only every Haneke fan or every film lover but every mortal being concerned by his or her aging and mortality should watch Amour. As usual, Haneke strikes deepest through simplicity. He proves once more that no complicated storyline is needed to have drama. He builds up the tension of his film just by pointing his camera to human existence and documenting (in excruciating detail) its fading away. The story is about an old couple of musicians living in Paris. The woman suffers a number of stokes and slowly but inevitably disintegrates in front of her husband desperate to hold on to her the way she was and genuinely torn by her suffering and slow death.

Haneke is one of the most sincere and straight-forward directors – he gives you no bullshit and no fake comfort, but throws everything in your face: all the embarrassing malfunctions of the body, all the annoying character flaws, and all the desperate but necessary gestures that emerge in a limit-situation.

The cinematic style of other Haneke films has been perfected and purified in this one: strong acting, deep philosophical insight and drama and an utter refusal to compromise in order to comfort anyone. Acting by veterans Emanuelle Riva (Hiroshima, mon amour) and Jean-Loius Trintignant (The Conformist, Z), as well as from Haneke’s twisted muse Isabelle Hupert (La pianiste)is flawless as always. We also have the characteristic provocative ending that has become a trademark of Haneke films – but of course, given the premises of this film, it is not a major spoiler to reveal that the ultimate punch line of the film involves death and dying.

The strongest features of the film, however, are beyond the formal, stylistic or reflective – these we already became accustomed to and wouldn’t accept less from Haneke. In previous films, Haneke dissected universal phenomena almost abstracted to their essence: violence, fear, religious, nationalistic or racist fanaticism. These were of course not abstract conceptions for him, but his characters were rather abstract exemplifications or tools towards saying something important and revealing about his very much real issues. In this case, however, the characters are all present in their own personal uniqueness. And it is no accident that this is the case: for a radically sincere director like Haneke aging and death cannot be addressed without the physical, actual, biological process of dying. And this bodily event of death makes it impossible for his characters to remain abstract. Especially Riva gives an incredibly courageous performance in this respect. So everyone living through their own gradual dying or helplessly witnessing the demise of a loved one cannot be anything else but a unique person. In our death we become irreplaceable, even though we are all dying. We cannot take on someone else’s death, even if we wanted to.

The film’s couple is approaching the end of their lives. Their tragedy is not only this, but also that they are dying at different speeds: she is disintegrating fast, first as an organism, then, inevitably, also as a person. He has to watch her slip away, take care of her basic needs and face his own end all at the same time. Haneke and the actors manage to allude to the deep love and intimate bond between the man and the woman with just a few simple words or gestures. No big declarations of love are needed, it is clear almost from the start that these to people belong together in the deepest possible senses that a person can belong to another. The ultimate gesture at the zenith of the film is also ultimately a gesture of love – hence the title of the film. Although this is a film depicting dying, it is essentially about love, or about how love figures or matters in certain death. We are reminded of Alejandro Amenabar’s Mar adentro, where the main character says: “The person who really loves me will be the one who helps me die. That’s love.”

But the love between the man and the woman is not the only love challenged by sickness and death. They have a daughter and the relationship between parents and child is also addressed in the most ruthless fashion by Haneke. The daughter’s life and problems seem very far away, foreign, impossible to relate to (even silly at times). But the opposite is also true: she can not understand what it means to stare certain death in the face every day – not to mention in the face of a loved one. Thus her presence seems to be an intrusion every time. This lack of connection between parents and daughter is all the more painful as it happens in spite of the obvious love and affection that they have for each other. It is as if saying that love is not enough if it does not share the same physical and existential space: the parents are facing a limit situation, and there is no room for advice or pity from anyone else. At one point the father utters the harshest words to his daughter: “Why don’t you just leave us alone to die here in peace.” This is not necessarily a reproach that she doesn’t understand as a genuine wish to dedicate all of his attention and efforts to the last days as living beings.

The existential isolation in the face of death is also expressed spatially. Other than a brief scene at the beginning, when they are both well, the entire film takes place in one apartment which becomes a suffocating, different plane of existence. I read in an interview that the apartment was made following the exact layout of the apartment where Haneke’s parents lived, although the furniture was not the same. As if he needed the architectural structure of that apartment – the sketch of it – but not the exact replica to tell his story. What matters are the walls that separate – first of all from the rest of the world, but then also within the apartment – as she becomes more and more sick, her presence she is restricted to less and less territory (ultimately to the bed), while he becomes more and more lonely and foreign in the rest of the apartment.

Although the outside world is still occasionally and even significantly present in the form of neighbors, relatives, former students or nurses, ultimately, the couple is all alone here, and eventually, when he remains alone, he cannot stand to remain in the home he shared with her…Before the end, he has several nightmares, all of which are grim images of a deteriorating, horrific and flooded world outside the apartment and within their marital bed. The end of the film is open to interpretation, we do not find out what happened to the man or where he is. What we know, though, is that he did not remain there in that shared place. It is also as if it doesn’t even matter anymore…after her death, his life, even if it goes on, it doesn’t “count” anymore.

Béla Tarr’s latest opus, The Turin Horse is a rare cinematic and hermeneutic experience. It expects the viewer to be ready to enter into an open and thoughtful interpretative dialogue and filter the film through our own experiences and impressions. Tarr poses a question rather than offering an answer. Accordingly, the answers will be as different as many viewers are willing to join in. Visually, it is like watching an early Van Gogh painting (slowly) move. The same dark colors, similarly marked but almost expressionless faces, hands deformed by harsh work and a general atmosphere of hopeless resignation. But just as Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, Tarr’s characters – an old man and his daughter living on a remote farm – also manage to emanate an expressionless despair: a sense of being crushed and defeated by the harshness of existence but still performing daily routines just in order to exist, as if from inertia. The dull repetitive rhythm of everyday basic activities further deepens the claustrophobic and dark tone. This film is like the story of Sisyphus but without the dramatic dynamism of a moving rock and without the noble pride of revolt. It is also similar to Abe Kobo’s Woman in the Dunes, but without the possibility of genuine companionship or human ingenuity.

The man and his daughter (played by János Derzsi and Erika Bók) barely communicate; they are immersed in their own voiceless worlds where the only contact with each other is through the necessity of eat-sleep-drink. And even then, their communication is performed in routine movements, their mutual understanding and concordance is gestural – they continue each other’s movements and react in advance at each other’s unuttered needs. This bleak, senseless harmony is disturbed by the gradually disintegrating environment. Nature and the basic elements seem to revolt against humans – the water disappears from the fountain, the winds rise, animals die, and finally, light disappears, effectively signaling the end of the world. Except for a brief episode of revolt (which takes the form of an attempt to escape), the two characters react in a matter-of-fact way to such apocalyptic changes. When the world comes to an end, they quietly go to bed, accepting their fate.

Although the title is an allusion to a story about Nietzsche, I believe this film is not a reflection or interpretation of Nietzschean philosophy. Rather, it is precisely the story of the philosopher hugging an old horse and crying for it that is the starting point, the excuse, if you will, to contemplate that kind of visceral cry for living beings that is exemplified in the story. What was it about that old horse that made the philosopher who celebrated vitality and life break down in despair? Presumably the same basic human reaction to suffering and death motivated this film too. No matter how bleak or senseless or hopeless an existence is, its sheer presence, the fact that it is, and the certainty of its disappearance infuses one with deep sadness and melancholy.

Tarr seems to be stating and mourning the existence of living beings (humans and animals) at the same time. The realistic depiction of everyday activities contrasts the subtle symbolism and abstract manner of treating the environment outside the farm. Accordingly, I think there are two possible levels of understanding which gradually become intertwined in the film. The quotidian, almost unbearable repetition of the same movements and gestures points to an existential dimension: the pointlessness of life, freedom, language, the endless repetition and certain demise of all living beings. This daily rhythm (and the silence accompanying it) is broken three times: once by the visit of a neighbor, then by the arrival of some Gypsies, and finally, by an attempt to flee the farm. In the first two cases the outside world challenges the characters in the form of other humans, while in the third the characters try to break away by running toward an outside world. However, by this point, the cosmic dimension has already gained major influence. There is nowhere to run; any attempt to escape is pointless – the threat is not local and not personal. Thus the second level of understanding offered by the film is a cosmic one: we are witnessing the end of the world and just as the characters, there is nothing we can do. Compared with this cosmic event, the fate of humans shrinks in importance. What is the demise of an already mortal being in comparison with the disappearance of the world?

Nietzsche cried for that horse although the horse presumably was not aware of the tragedy of its own being – or maybe that is precisely why he cried. In the film we cannot help being deeply moved by the disturbing inertia of father and daughter, by their voiceless, senseless and unreflected existence. In each case, it is not sure and clear what it is that we are crying about: the dull senselessness of life, or its end, dull and senseless as it is.

Cristi Puiu is one of those directors who respect their audience. Although profoundly personal, at times even idiosyncratic, his latest film, Aurora seems to be an attempt to a dialogue with the audience and also, an attempt to hold up a mirror to all of us watching. How does a person end up killing someone? What would it take for me to kill someone? And how would a person have to be in order to decide and be able to kill someone? Does it take a certain type of person? Could you tell, if you were his neighbor? Or does it take a certain type of society, a certain type of inter-personal life (or the lack of it) to drive someone to murder?

Puiu does not make it easy for his audience to follow his film or his hero (excellently played by Puiu himself – hence another idiosyncratic aspect). This is one of those rare films that necessitates patience but rewards it plentifully by slowly captivating the viewer and, what is most important, at least for me, by becoming reflexive: drawing attention to the viewing experience, thus making the film as much about the hero as about the viewer. How are we present among people around us? How do we see them? How do they see us?

The main feature of the film, as I see it, is the brilliant camerawork. And this is because the camera succeeds in inducing a paradoxical double effect of an intruding intimacy and exclusion at the same time. It made me feel like I was too close and still missing out on something. Sometimes the camera is like a person, wandering and lingering around the scenes, aimlessly, not quite sure why. Other times it becomes an inert object, accidentally left on a piece of furniture or in a corner and it seems it just happens to record whatever is right in front of it. If this is a wall and half of a door opening, so be it. This complex camerawork achieves the paradoxical effect I mentioned before.

The camera provides intimacy, a sense of being there, close to the hero and the events. But this intimacy is not the “all-knowing” godlike perspective of a Hollywood audience. It is more of an intruding intimacy which comes with the sense of “I am not supposed to be here”, the guilty intimacy of peeping on your neighbors. We are there in the film as a real person would be in one of the rooms in the guy’s apartment or on the streets where he walks. And as such, we don’t follow him everywhere; sometimes when he goes to the kitchen, we don’t go after him; sometimes we hear fragments of his conversation without quite understanding what he is talking about. We sometimes see and hear things without quite knowing how to piece them together. And this induces the second, more frustrated impression. This kind of realistic camera-presence makes us anxious, frustrated, impatient at times. With all the closeness, we still can’t see, we still can’t hear and we still can’t understand.

So the film seriously challenges our “fill in the blanks” capacities. As a film-fool, first I tried to guess what was going on relying on film precedents. My mistake was that I tried to understand the guy as a character in a film. The frustration came from the fact that we were thought and conditioned to expect a coherent, explanatory narrative from a film. We got used to things being spelled out for us, for example people talking to each other and mentioning their relation to each other (so that the audience knows) or the antecedents of their conversations (so that the audience understands). But real people around us don’t talk like that, do they? We don’t talk like that. We don’t follow people around us everywhere, not even when they are close family members, we don’t go after them every time they walk out of the room we are in.

But then again, we rarely follow strangers into the shower. That is why the long shower scene shocks with its intimacy and closeness. Precisely as until then the camera has created that realistic yet paradoxical intimacy-intrusion mood, watching the guy shower and check his testicles for lumps comes as almost an embarrassment for the audience. How would you feel if you happen to catch your neighbor doing that?

That is how, slowly the realistic atmosphere of the film sucked me in and I completely forgot about other films. I became that frustrated neighbor, half-enjoying peeping in, half-embarrassed by being there and all the time quite frustrated for not being able to understand. I was faced with my own incapability to understand the people around me. I was forced to think about all the people I pass by or come in daily contact with, yet still know nothing about them.

All in all, the atmosphere of the film reveals the strangeness and otherness of the other, the impossibility to penetrate into another consciousness and state of mind, no matter how close and intimate we get to it physically. If anyone expects the portrait of a murderer, he are she will be quite disappointed. What we get is the portrait of a person who feels very real and very close and who just happens to be a murderer. We don’t get nicely coherent psychological explanations; we don’t get to understand the reasons behind the murders. In the end, we are left, again, in the role of the eternal neighbor who, when asked by the police or the press declares himself surprised as the murderer “seemed like a nice, quiet, ordinary person”. And the point is not to suggest that anyone of your neighbors could be a murderer, but to pose the question: could you be one? Could it be that we live so close to each-other yet so far away that our contacts with each other remain at the level of peeping in and watching each other move about?

The final scene at the police department is in a quite sharp contrast with the rest of the film. It is almost like an ironic laugh-in-the-face in which Puiu offers some factual information to the frustrated viewer, as if asking: there, now you know these facts, does it help you understand? Does it make you care more? And judging by the attitude of the police, knowing all the facts certainly doesn’t make us care. The detectives are more preoccupied with their immediate, mundane problems (a disputed parking space, a misbehaving coffee machine). Isn’t this also our excuse for not knowing and not caring enough about each other? Aren’t we all too sucked into our missed buses, leaking installations and petty business? No wonder then that for the police murder seems to be just a collection of facts gathered according to a form that must be filled out, the beginning of a formal procedure through which, no doubt, the murderer will be charged, condemned and sentenced to prison. Nobody cares about the guy’s reasons, he is repeatedly instructed to stick to the facts, state his ID number and address, the names of the victims, the place and time of murder. The comedy effect of this scene is all the more disturbing as it is inevitable. Why are we laughing? Who are we laughing at?